Are our phones listening to us?

‘Coincidental’ ad placement raises questions about cell surveillance

You and a few friends are hanging out for the night. Your one friend talks about how badly she needs a new winter coat while your other friend compliments you on your new pair of leggings. After singing to the newest Taylor Swift song at the top of your lungs, you have an ever so slight debate on where to eat–Subway, Pizza Hut, or B-Dubs.

A few minutes later, you get an ad for Fabletics leggings on your Instagram page.

An hour later, your YouTube video is interrupted with an ad for Taylor Swift’s newest album.

The next day an ad for Pizza Hut is plastered across your Google searches.

You can’t help but wonder, is your phone listening to you?

In its earliest forms, advertisements were a two-inch by two-inch graphic on the second page of the Sunday paper, making it nearly impossible for marketers to target an ad to a specific audience while ensuring its relevance to those receiving it. But with the emergence of modern technology, marketers can pinpoint the exact audience for a product with rather unsettling accuracy.

Nowadays, it seems all it takes is one mention of a product for it to be plastered across your social media apps, internet searches, and everything in between. Despite this shared phenomenon amongst most users, large companies have spoken otherwise.

“Facebook does not use your phone’s microphone to inform ads or to change what you see in News Feed,” Facebook said in a recent statement. “Some recent articles have suggested that we must be listening to people’s conversations in order to show them relevant ads. This is not true.”

The statement went on to explain that Facebook targets ads based on a person’s personal profile, including their age, gender, interests, etc. Other companies are also known to build eerily accurate profiles using a person’s purchase histories, locations, race, income, and education without ever tapping into a user’s microphone.

To put these statements to the test, I ran an experiment of my own, selecting a few products and brands to both speak of and search up online, recording any coinciding ads I received.

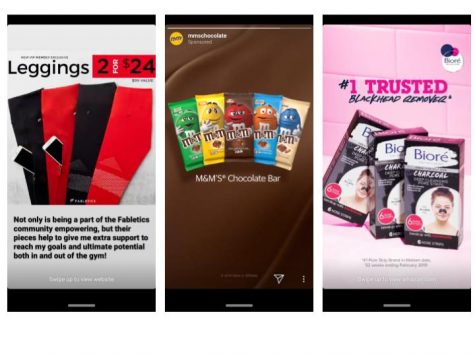

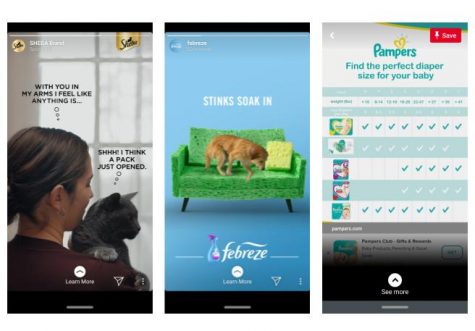

Because companies like Instagram and Facebook claim to select ads based on the user’s personal profile, I ran two separate experiments: one in which the products were relevant to my “user profile” (leggings, M&Ms, and skincare) and one where they were not (diapers, cat food, and Febreeze). I then started bringing up these products in my everyday conversations, mentioning them sporadically here and there a couple of times a day while consistently making sure to have my phone around me.

The results might make you think twice about how your phone collects your personal data.

Within one day, I started seeing ads of the very products I had conversations about, including those such as diapers and cat food that are nowhere within my “user profile.” In just three days, all six of the products I had mentioned appeared across my Instagram, Snapchat, Pinterest, and YouTube accounts.

Never once did I Google these products or search them across social media.

I’m a 16-year-old girl.

Diapers should be nowhere in my “user profile.”

As uncanny as it might seem, Marketplace.org claims there might be another explanation for what seems like a not-so-coincidental coincidence. Called the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon it’s the idea that once something is brought to our attention, we start to see it everywhere, suggesting that those ads for diapers might have been there before, I just never seemed to notice until it was brought to my attention.

So maybe our phones aren’t really listening to us. Maybe it is the elusive algorithm formulating user profiles to target particular ads. Or maybe our brains truly are playing tricks on us, making us notice things that weren’t there before.

Or maybe not.

Either way, one thing is for sure: our phones “know us.”

Remmington is a senior at Carroll. This is her third year on the newspaper staff and second year as co-editor in chief. She is an avid writer...